Now Reading: Logical vs Physical Data Models: Key Differences and Uses

-

01

Logical vs Physical Data Models: Key Differences and Uses

Logical vs Physical Data Models: Key Differences and Uses

Introduction

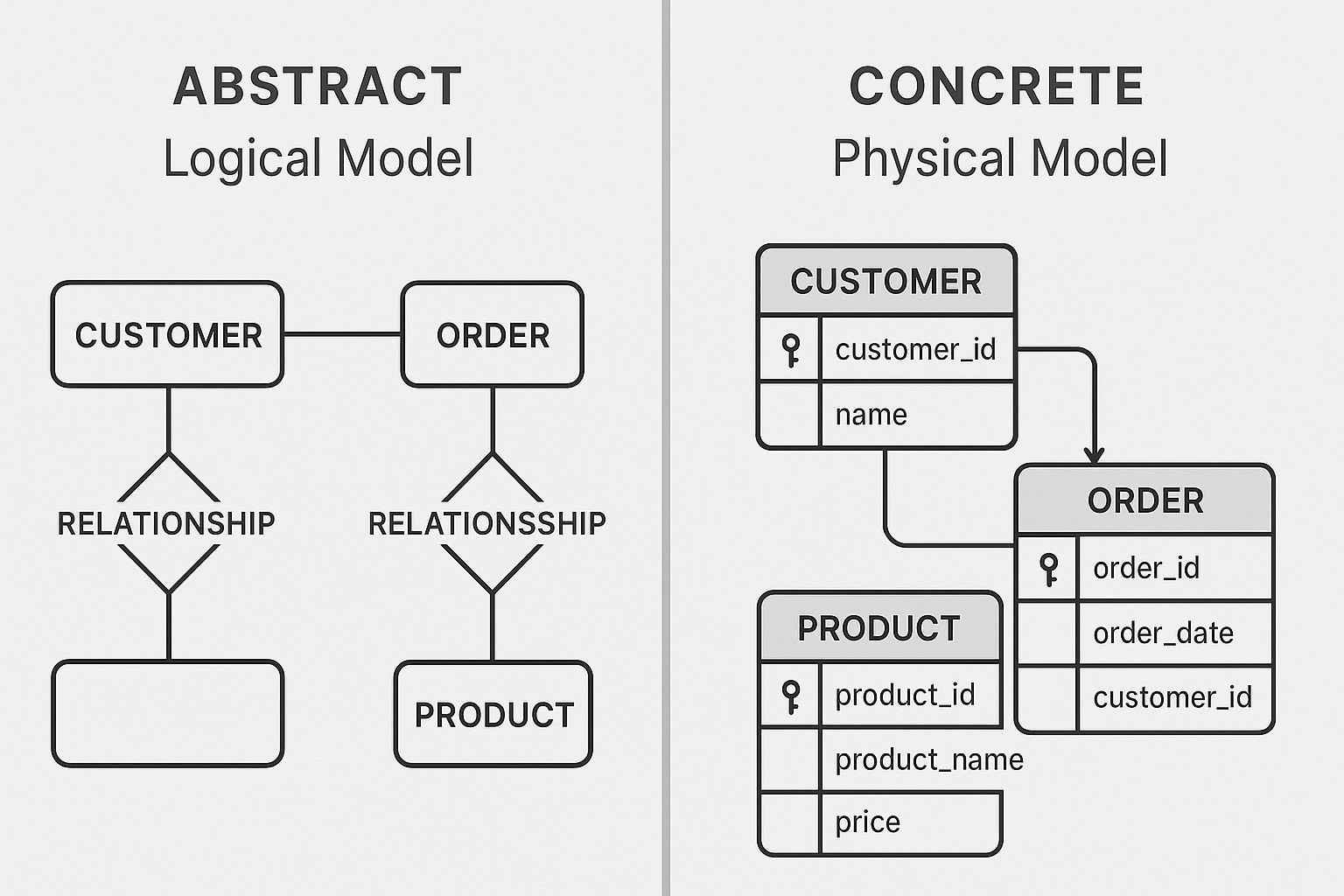

In modern data-driven organizations, the way we design data relates directly to how effectively we can extract insight, scale systems, and govern information. Two foundational viewpoints shape these design conversations: logical data models, which capture business concepts and rules in a technology-agnostic form, and physical data models, which translate those concepts into concrete structures optimized for storage, performance, and reliability. Understanding the distinctions between these models — and how they relate to the design and implementation phases — is essential for teams that must align business strategy with data architecture.

This article examines logical versus physical data models through a business-technical lens. It explains what each model represents, what problems it solves, and how organizations typically navigate the transition from high-level business concepts to the concrete database artifacts that run in production systems. The goal is not to declare a winner but to illuminate where each model adds value, where they intersect, and how disciplined modeling supports governance, analytics, and scalable design.

What is a Logical Data Model?

A logical data model represents the business domain independently of any specific technology or database platform. It focuses on describing the meaning of data, the relationships between concepts, and the rules that govern data integrity from a business perspective. The emphasis is on understanding what data exists, how it relates, and how it will be used by analysts and decision-makers, rather than on how it will be stored or indexed.

Core characteristics of a logical data model include a stable vocabulary, clearly defined entities and attributes, and relationships that reflect business realities. Because it abstracts away physical constraints, a logical model is highly adaptable to evolving requirements and can serve as a common language across stakeholders, data stewards, and developers who will later implement the model in a physical database. It acts as a contract that guides data governance, data quality, and onboarding of new data sources.

- Abstraction from technology: the model remains valid regardless of the underlying database or storage mechanism.

- Business-centric entities and attributes: names and definitions align with business concepts, not data types or table structures.

- Normalization and relationship semantics: emphasis on how data is related, including cardinalities and optionality.

- Business rules and constraints: rules about validity, consistency, and derivation that can be implemented later in governance or ETL steps.

- Evolution and governance readiness: designed to adapt as business requirements change, with clear ownership and provenance.

- Platform-agnostic collaboration: a shared vocabulary for business analysts, data stewards, architects, and developers.

What is a Physical Data Model?

A physical data model translates the abstract concepts from the logical layer into concrete structures tailored for a specific database technology and deployment environment. It details how data will be stored, indexed, partitioned, and accessed, including table definitions, column data types, constraints, storage parameters, and performance-oriented configurations. The physical model is the blueprint used by database administrators and engineers to build and optimize the actual data substrates that support applications and analytics workloads.

The physical model reflects technical realities such as the capabilities and limitations of chosen database systems (for example, relational databases, columnar stores, or data lake architectures), hardware constraints, and operational requirements like backups and failover. It also embodies decisions about performance tuning, data distribution, and data lifecycle management, translating business concepts into an implementable schema while balancing stability, scalability, and cost.

- Technology-specific design: the model accounts for the features and constraints of the chosen database platform.

- Tables, columns, and data types: concrete structures that determine storage layout and data representation.

- Indexes, constraints, and physical keys: mechanisms to optimize query performance and ensure data integrity.

- Partitioning, clustering, and distribution: strategies to scale storage and I/O across nodes or storage tiers.

- ETL/ELT mappings and data lineage: explicit data flows from source to target, including transformations.

- Operational considerations: backup strategies, recovery objectives, and maintenance windows.

Key Differences Between Logical and Physical Models

The most effective data architecture emerges when teams recognize what each model emphasizes and how they complement one another. The table below highlights representative contrasts that practitioners frequently use to guide discussions and decisions:

| Focus | Logical: Business concepts, meanings, and relationships in a technology-agnostic form. |

| Abstraction level | Logical: Higher-level abstraction to protect business semantics from implementation details. |

| Artifacts | Logical: Entities, attributes, relationships, and business rules; no physical storage specifics. |

| Technology dependency | Logical: None; independent of database engines or hardware. |

| Design goals | Logical: Clarity, consistency, and governance of business data concepts; platform neutrality. |

| Implementation details | Physical: Data types, tables, indexes, partitioning, and performance tuning. |

| Optimization focus | Physical: Storage layout, access paths, and throughput under real workloads. |

| Evolution | Logical: Stable business rules with the ability to evolve as requirements shift; physical evolves with technology and scale. |

| Stakeholder audience | Logical: Business analysts, data stewards, and architects; Physical: DBAs, data engineers, and developers. |

When to Use Logical Data Models

Organizations typically begin with a logical model during the early stages of a data program or analytics initiative. The goal is to align business understanding, establish common definitions, and set the stage for scalable design before committing to a specific technology stack. Logical models serve as a lingua franca that helps diverse stakeholders agree on what data means, how it relates, and how it should be governed. They are especially valuable in contexts where requirements are evolving, new data sources are being onboarded, or multiple departments must share a consistent data vocabulary.

In addition to guiding governance and collaboration, logical models enable teams to validate high-impact design choices without incurring the overhead of physical implementation. They support scenario planning, impact analysis, and traceability from business concepts to analytics outputs. When business questions are the priority, and speed to consensus matters, a well-constructed logical model provides a solid foundation for later technical translation.

- Early discovery and requirement capture: define business terms, entities, and relationships before selecting technologies.

- Platform-agnostic design: keep choices open to accommodate future data platforms or analytical tools.

- Stakeholder alignment and governance: establish a shared vocabulary that persists as teams scale and data sources proliferate.

- Change management discipline: create a flexible model that can absorb business rule changes without breaking downstream implementations.

When to Use Physical Data Models

Physical data models come into play once the decision is made about concrete technology and deployment strategies. They translate the agreed-upon business concepts into implementable structures that meet performance, reliability, and operational requirements. The physical model is where engineering discipline, database capabilities, and operational realities converge. It is essential for ensuring that data can be stored efficiently, queried quickly, and maintained reliably in production environments. A well-designed physical model also reduces the risk of bottlenecks, data quality issues, and costly rework during deployment or migration.

Typical drivers for adopting a physical model include explicit performance targets, storage constraints, data quality SLAs, and the need to support specific reporting or analytics workloads. As organizations mature in data capability, the physical model becomes a living artifact that reflects tuning efforts, indexing strategies, and data lifecycle decisions. It provides a concrete blueprint for developers and operators to implement, optimize, and monitor data flows end-to-end.

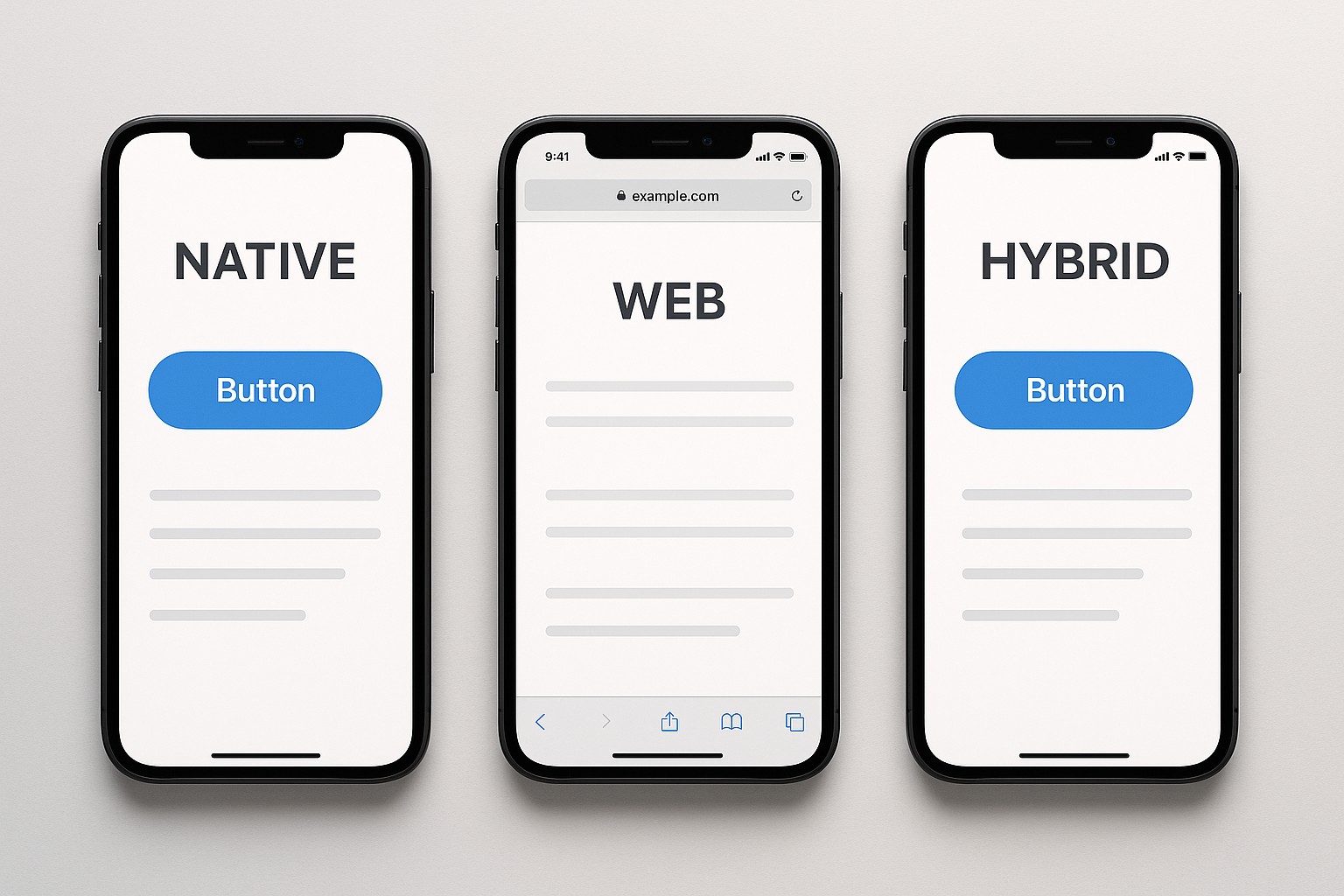

- Technology and platform decisions: select a database engine and architecture (relational, columnar, or hybrid) and model accordingly.

- Performance and scalability: design for query patterns, throughput, and concurrent access with appropriate indexing and partitioning.

- Data integrity and lifecycle: enforce constraints, define data lineage, and plan archival/retention policies.

- Implementation-driven requirements: specify data types, constraints, and storage parameters to support production workloads.

- Operational readiness: align with backup, disaster recovery, monitoring, and change management processes.

Bridging Logical and Physical: From Concept to Reality

Bridging the gap between logical and physical models is a structured, iterative process. Teams typically map each logical entity to one or more physical tables or data structures, define concrete attributes with data types, and determine how relationships translate into foreign keys or join paths. The careful handoff requires ongoing collaboration among business analysts, data architects, and data engineers to maintain fidelity to business semantics while achieving practical performance and maintainable schemas.

“The strongest data architectures align business meaning with technical capability, ensuring data remains trustworthy, discoverable, and usable as it moves from concepts to systems of record.”

To support this bridging, it is common to establish a modeling protocol that captures decisions, rationale, and trade-offs at each step. This protocol helps teams document assumptions, trace requirements, and revisit designs when new data sources appear or when analytics use cases evolve. When done well, the transition preserves the integrity of business definitions and delivers a robust, scalable implementation that can adapt to changing technology landscapes.

Case Study and Practical Considerations

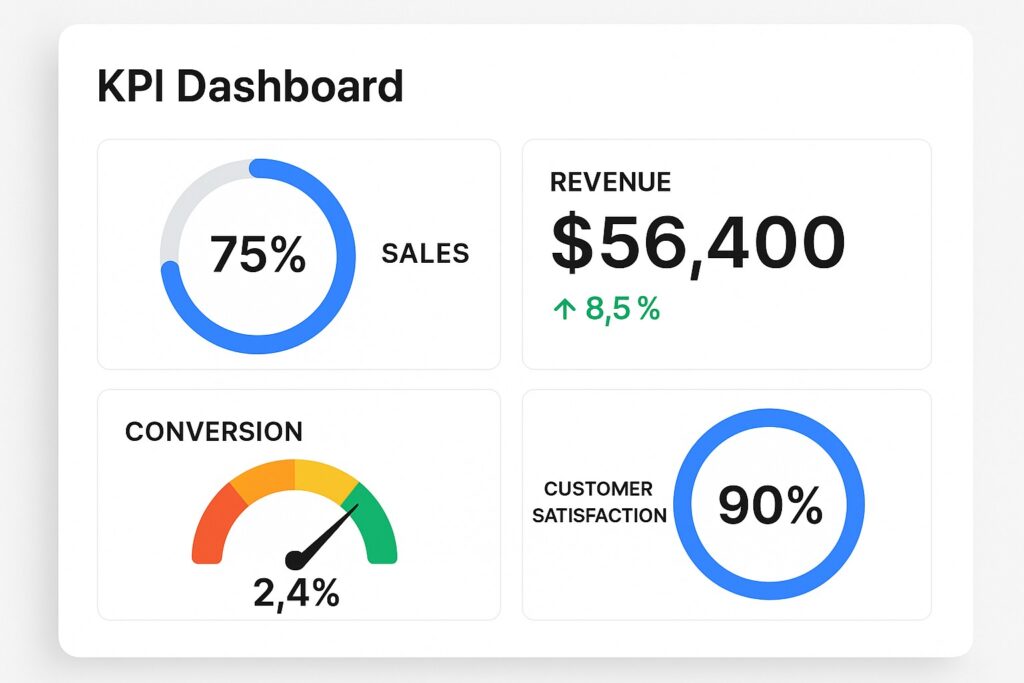

Consider a multinational retailer launching a data platform intended to support executive dashboards and advanced analytics. The data team begins with a logical model to capture core business concepts such as customers, products, sales, promotions, stores, and time. The model defines relationships like customers place orders, products belong to categories, and stores operate in regions, with rules about currency, pricing, and loyalty status. This phase provides a clear picture of what data the organization cares about and how it should be interpreted across markets.

When the organization moves to the physical design, it chooses a database platform aligned with both analytic workloads and operational needs—perhaps a hybrid approach combining a columnar store for analytics with a transactional relational store for operations. The physical model then dictates table definitions, appropriate data types, indexing strategies for fast aggregations, partitioning to manage large fact tables, and ETL/ELT pipelines that transform source data into a form suitable for reporting and analytics. The end result is a production-ready schema that honors the business semantics captured in the logical model while delivering the performance and reliability required by the business.

Practical considerations during this phase include data quality governance, data lineage, privacy and compliance constraints, and the need to accommodate frequent changes in promotions, pricing strategies, and regional variations. Teams should plan for governance reviews that ensure the physical design does not compromise the semantics that the business defined earlier. They should also establish testing regimes to validate that reports and analyses remain accurate as the data evolves.

Best Practices and Common Pitfalls

Organizations that excel at data modeling tend to follow a disciplined set of best practices. They emphasize collaboration, maintain a clear separation between logical and physical concerns, and implement governance processes to manage changes across both models. At the same time, they avoid common traps such as conflating business requirements with storage optimizations too early, over-normalizing to the point of impractical joins, or under-planning for data quality and lineage. The best teams continuously refine both models in parallel, ensuring alignment as business priorities shift and as technology capabilities expand.

Key considerations include establishing a common vocabulary across stakeholders, documenting business rules in a way that can be translated into data quality checks, and designing physical schemas with flexibility to accommodate future data sources and analytics workloads. Another important practice is maintaining traceability from business concepts to data artifacts, so that analysts can understand how a data point is defined, transformed, and consumed in various reports and dashboards.

Towards a Practical Implementation: A Lightweight Example

To illustrate how logical and physical models interact, consider a simplified mapping example. In the logical model, you might define a Customer entity with attributes such as CustomerID, Name, Email, and LoyaltyTier. In the physical model, this could be translated into a table named dim_customer with columns such as customer_id (primary key), full_name, email_address, and loyalty_tier_code. The relationship between Customer and Orders in the logical model would map to a foreign key relationship from the fact table (fact_order) to dim_customer. The conversion also informs decisions about indexing on customer_id, the choice of data types that reflect real-world values, and the introduction of surrogate keys for stable joins in a distributed environment.

// Pseudo-DDL illustrating a simple physical design transition

CREATE TABLE dim_customer (

customer_id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

full_name VARCHAR(200) NOT NULL,

email_address VARCHAR(255) UNIQUE NOT NULL,

loyalty_tier_code CHAR(2) NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE fact_order (

order_id BIGINT PRIMARY KEY,

customer_id BIGINT NOT NULL,

order_date DATE NOT NULL,

total_amount DECIMAL(12,2) NOT NULL,

FOREIGN KEY (customer_id) REFERENCES dim_customer(customer_id)

);

CREATE INDEX idx_order_date ON fact_order (order_date);

FAQ

What is the main difference between logical and physical data models?

The main difference lies in purpose and level of abstraction. A logical data model focuses on business concepts, relationships, and rules without tying them to any technology. A physical data model translates those concepts into concrete database structures, with specific tables, columns, data types, and performance-oriented design choices that reflect the capabilities of a chosen platform.

Can a logical model be directly implemented in a database?

Not typically. While a logical model provides a clear blueprint of business concepts, implementing it directly would ignore technology constraints and performance considerations. Organizations usually create a physical model that maps the logical concepts to database structures and then implement it in a database system, often iterating to preserve business semantics while meeting technical requirements.

How do data governance and compliance affect model choices?

Governance and compliance influence both models, but they are especially impactful during the logical phase, where business rules and data lineage are defined. Clear governance helps ensure consistent terminology, controlled vocabulary, and traceability from source to analytics. In the physical phase, governance governs data quality checks, access controls, retention policies, and auditing mechanisms that enforce compliance in production systems.

How do you transition from a logical model to a physical model?

The transition typically involves collaboration between business analysts, data architects, and engineers. The process includes mapping entities and attributes to concrete tables and columns, selecting data types based on data characteristics and platform capabilities, defining keys and constraints, designing indexes and partitions, and planning ETL/ELT processes that implement data flows while preserving business semantics and governance rules.

What role do analytics use cases play in choosing a model?

Analytics use cases drive both modeling paths but in different ways. Logical models help capture the questions analysts want to answer and ensure consistency across analyses. Physical models are tuned to support the performance and scalability needs of those use cases, ensuring that queries run efficiently on large data volumes. A well-aligned approach uses a robust logical model as the blueprint and a performant physical model as the operational engine behind analytics workloads.