Now Reading: Prototype vs MVP vs POC: Defining Project Stages

-

01

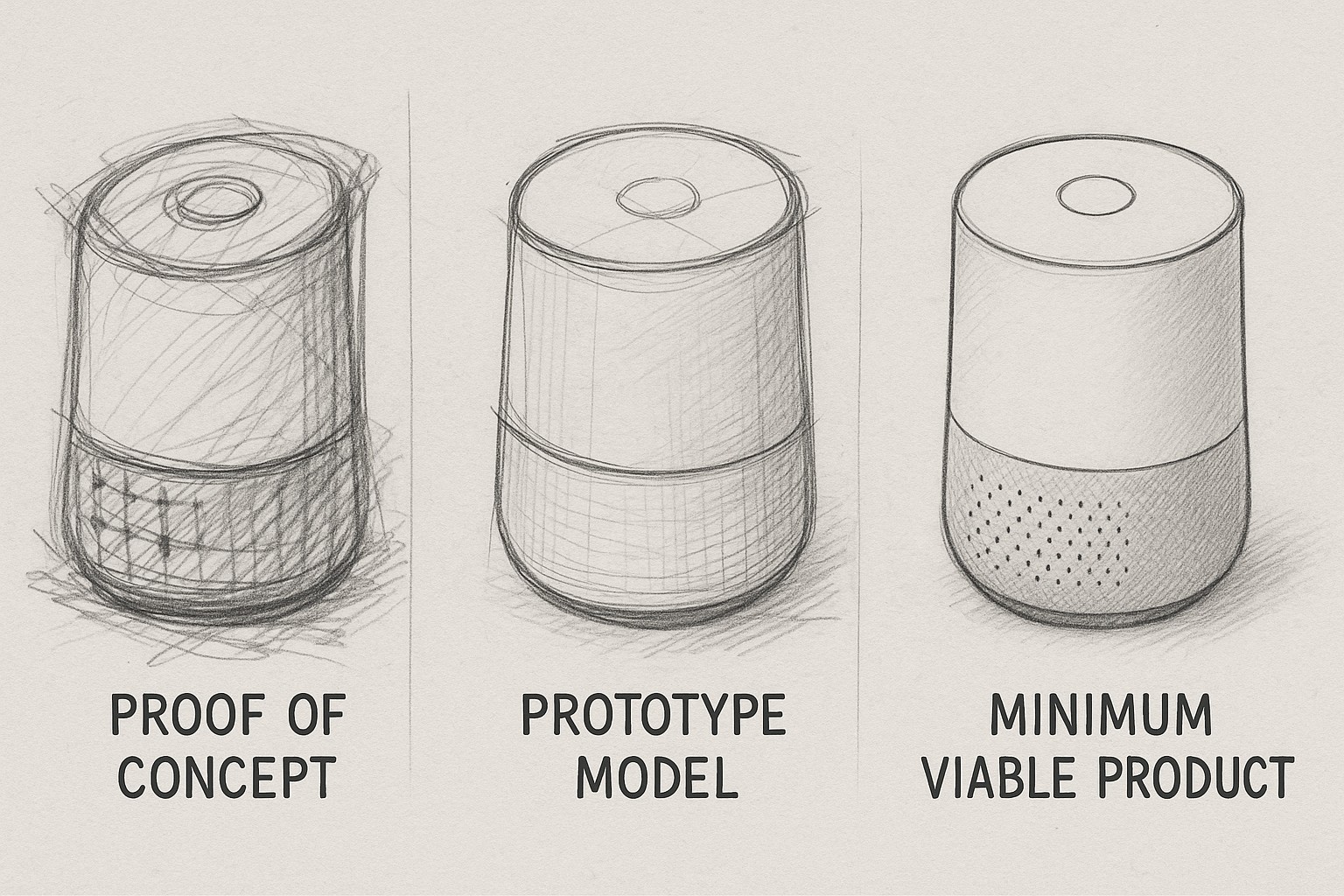

Prototype vs MVP vs POC: Defining Project Stages

Prototype vs MVP vs POC: Defining Project Stages

Proof of Concept (POC): Definition and Purpose

A proof of concept is a focused exploration designed to verify that a specific idea or approach is technically feasible within the context of a proposed solution. In practice, a POC aims to answer a narrow question: can this concept work with the current data sources, technology stack, and integration points? It is not intended to be a finished product, nor a demonstration of user experience; rather, it serves as a risk reducer that helps stakeholders decide whether to invest in broader development. In agile testing processes, a POC is often the first concrete step that converts hypotheses into tangible signals, guiding subsequent decisions about scope, architecture, and resourcing.

A POC is typically timeboxed and deliberately scoped down to address the riskiest assumptions. The outcome is usually a concrete technical artifact or a demonstration of key capabilities, such as integrating a new API, proving model accuracy on a representative dataset, or showing that a component can operate within performance constraints. Because the goal is feasibility, success criteria focus on technical feasibility, performance benchmarks, and the viability of further investment rather than user value or market demand. The POC thus serves as a decision trigger: if the concept proves viable, teams can move forward with greater confidence; if not, stakeholders can pivot without committing substantial resources.

Key differences from prototypes and MVPs are worth noting. A POC is not a product, nor is it expected to expose a user flow or satisfy end-user needs. It may involve a small, isolated codebase or a restricted integration, and it is often throw-away work intended to be discarded after the learning is captured. The POC helps frame architectural choices and interfaces, and it highlights potential showstoppers early in the discovery phase. When used well, a POC shortens the path to a validated concept and accelerates informed bets about whether to pursue deeper exploration, prototype work, or a full MVP.

- Limited scope to test a specific risk or assumption

- Non-production code; typically throw-away after learning

- Timeboxed to a matter of days or weeks

- Demonstrates technical feasibility to stakeholders and decision-makers

- Not intended to measure user value or market demand

- Cross-functional collaboration to surface risks and dependencies

Prototype: From Ideas to Tangible Interactions

A prototype is a step toward validating how a concept will feel and behave from a user perspective. It can range from simple paper or clickable wireframes to high-fidelity, interactive experiences that simulate core features. Prototypes focus on user flows, UI decisions, and the feasibility of delivering expected interactions. They provide a realistic preview of the product experience without requiring a fully engineered backend or production-ready code. In agile teams, prototypes help stakeholders visualize ideas, align on requirements, and gather early feedback to refine design hypotheses.

The value of a prototype lies in its ability to elicit qualitative learning about usability, navigation, and perceived value. It accelerates conversations among product, design, and development teams and often reduces the risk of costly rework later in the build. While a prototype can involve working code, it is not intended to be scalable, secure, or robust enough for production. Instead, it serves as a conduit for validating how the product should work and how users will interact with it, often informing the scope and prioritization of the subsequent MVP.

Prototypes vary in fidelity to match the decision at hand. A low-fidelity prototype can quickly test concepts and gather initial reactions, while a high-fidelity prototype might closely resemble the final product’s look and feel, enabling more realistic usability testing and stakeholder demonstrations. Regardless of fidelity, the prototype should be treated as a learning instrument, not a shippable product. In many teams, prototype work is a prerequisite to MVP planning, helping to crystallize requirements and reduce ambiguity before committing to building a production-grade solution.

Common prototype purposes include validating user journeys, testing design decisions, and confirming the viability of interactions across devices. A well-crafted prototype also serves as a powerful communication tool for the broader organization, clarifying expectations and aligning timelines. By isolating design risk and technical feasibility, prototypes support faster learning cycles and higher-quality decisions within agile timelines.

- Validate user journey and UI flows

- Test technical feasibility of interactions

- Gather qualitative feedback from users and stakeholders

- Serve as a communication tool for the team

- Can evolve into an MVP if findings justify further investment

Minimum Viable Product (MVP): Core Value Delivered to Early Adopters

An MVP represents the smallest, fully usable product capable of delivering a core value to real users. It balances minimality with enough stability to operate in production environments and to collect meaningful data about how customers actually use the solution. The MVP is deliberately scoped to validate critical hypotheses about problem-solution fit, willingness to pay, and adoption patterns. In agile practice, the MVP is the instrument through which teams learn quickly from real behavior, surface actionable insights, and set the stage for iterative improvements based on real-world usage.

Delivering an MVP requires disciplined prioritization: only features essential to solving the core problem are included, and any additional capabilities are parked for future iterations. The emphasis is on measuring outcomes—activation, retention, engagement, and business impact—rather than polishing aesthetics or broad feature coverage. An MVP exists to test assumptions in the market, validate pricing or monetization models, and inform a roadmap that optimizes the next set of investments. By focusing on validated learning, teams can reduce wasted effort and align product development with actual customer needs and preferences.

The MVP is not a test of perfection; it is a learning engine. It must be deployable enough to operate in real usage scenarios, yet flexible enough to evolve rapidly as data and feedback accumulate. The most successful MVPs reveal clear signals about product-market fit and guide subsequent iterations toward higher value and broader adoption. When executed thoughtfully, an MVP becomes a springboard for incremental enhancements, more ambitious features, and a scalable architecture that supports growth and variability in user demand.

- Delivers a core value proposition to early adopters

- Includes only features necessary to test hypotheses

- Built with scalable architecture to allow learning and iteration

- Centered on actionable metrics like activation, retention, and conversion

- A plan for next iterations based on feedback and data

Choosing the Right Stage for Your Product

The choice between a POC, a prototype, and an MVP hinges on uncertainty, risk, and the information needed to proceed. If the primary objective is to confirm a technical feasibility or to de-risk a critical assumption, start with a POC. If the goal is to refine user experience, validate design decisions, and ensure that flows align with customer expectations, a prototype is the appropriate instrument. When you’re ready to test real value, learn from actual users, and determine whether there is a viable business model, an MVP becomes essential. In agile environments, teams often cycle through these stages iteratively, using each to reduce risk and inform the next set of decisions with tangible evidence.

Practical decision-making guidelines can help teams sequence work effectively. Evaluate the level of technical risk and architectural impact before committing to a broader build. Consider user-facing risk and experience uncertainty when choosing a prototype approach. Assess market uncertainty, willingness to pay, and the potential for scale when deciding to pursue an MVP. Remember that the goal of each stage is to learn more about the problem, the users, and the market, not merely to produce artifacts. In this way, the process aligns with agile testing processes: quick feedback loops, incremental learning, and a bias toward action that moves the product forward.

FAQ

What is the main difference between POC, prototype, and MVP?

A POC tests whether a concept is technically feasible and worth pursuing, a prototype focuses on validating design and user interactions, and an MVP delivers the smallest set of working features that allow real users to solve a core problem and provide data to guide next steps. Each stage serves a distinct learning objective: feasibility, usability, and market validation, respectively.

When should a team pursue a POC instead of a prototype?

Choose a POC when the highest priority is confirming that a technical approach or integration is possible within the current constraints. If the primary risk is how users will interact with the solution rather than whether the concept works technically, a prototype offers more value by testing design decisions and usability early.

How should user feedback factor into each stage?

In a POC, user feedback is typically minimal and focused on stakeholders or technical evaluators. In a prototype, user feedback is central, guiding design refinements and interaction flows. In an MVP, user feedback is continuous and data-driven, informing both feature prioritization and business decisions.

Can a product skip POC or prototype and go directly to MVP?

Yes, in some cases, teams may skip POC or prototype when risk is low, the concept is straightforward, and there is high confidence in the technology and user experience. However, skipping stages can increase the chance of late surprises, so teams should weigh risk, time-to-value, and the cost of potential rework before jumping straight to an MVP.

How do you measure success at each stage?

For a POC, success is technical feasibility and a clear decision on next steps. For a prototype, success is the ability to validate usability and influence design decisions, often shown by user feedback and refined requirements. For an MVP, success is measured by market learning: user engagement, retention, conversion, and the extent to which the product demonstrates a viable value proposition.