Now Reading: Virtual Machines vs Containers: What’s the Difference?

-

01

Virtual Machines vs Containers: What’s the Difference?

Virtual Machines vs Containers: What’s the Difference?

What is a Virtual Machine?

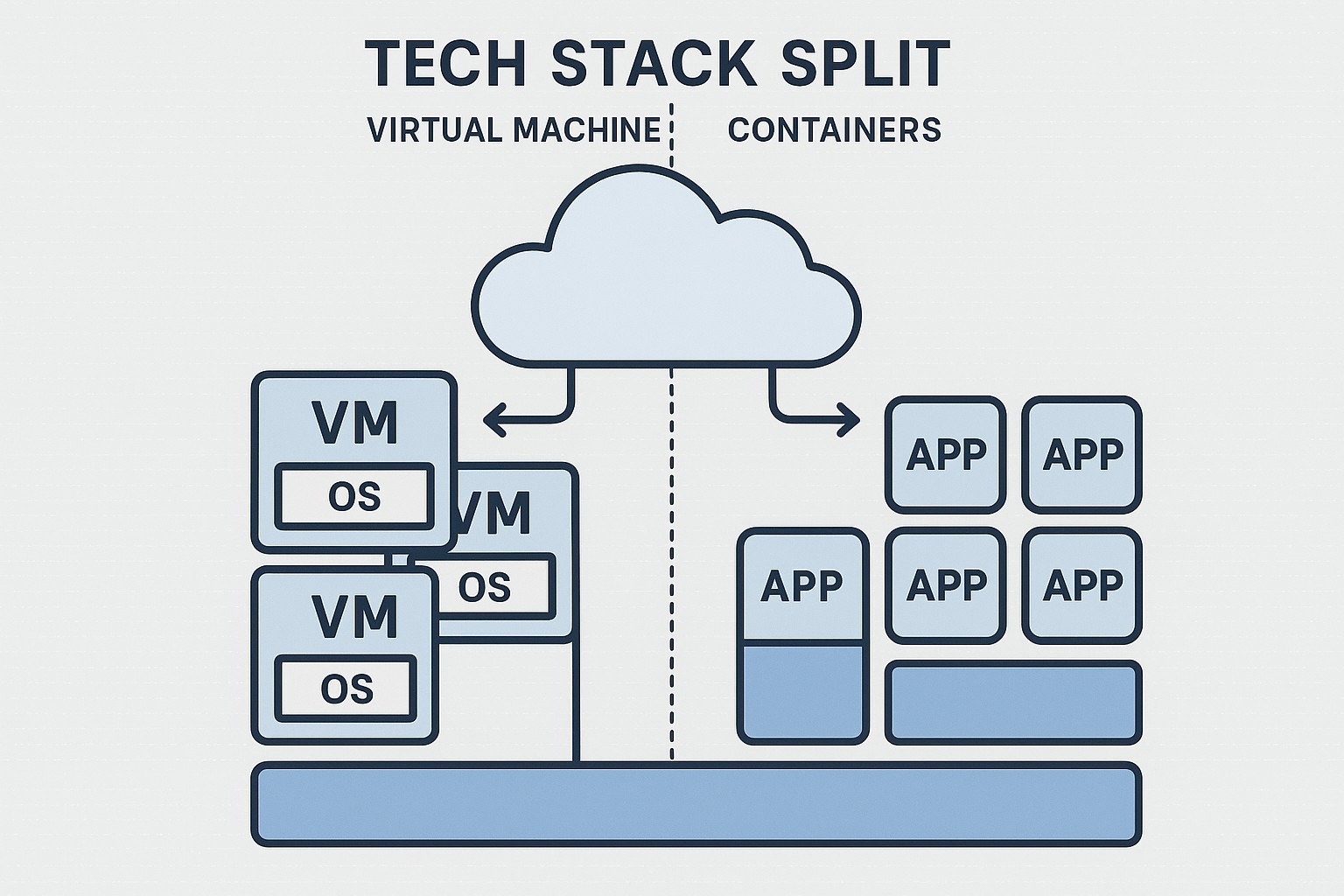

A virtual machine is an emulation of a complete computing environment that runs on physical hardware through a hypervisor. Each VM includes a full guest operating system, its own kernel, libraries, and applications, isolated from other VMs on the same host. This architecture provides strong boundaries, deterministic isolation, and compatibility with a wide range of operating systems and software stacks. For many mature, enterprise-grade workloads, VMs offer a familiar deployment model with established tooling for security, compliance, and governance.

In practice, organizations use VMs to encapsulate legacy applications, licensed software that requires particular OS versions, or scenarios with stringent regulatory requirements where a strong hardware- and hypervisor-enforced boundary is valuable. The separation between guest OSes reduces the blast radius of software failures within a VM, yet it comes at the cost of larger resource footprints and longer provisioning times. For teams managing heterogeneous environments, VMs can provide predictable performance and compatibility across diverse data-center or cloud regions, making them a durable starting point for many critical workloads.

- Separate kernel and system libraries per VM

- Full OS image per instance for strong isolation

- Hypervisor-enforced boundaries between VMs

- Ordinal boot times, typically minutes rather than seconds

- Broad compatibility with many operating systems and licenses

- Established management and security tooling in many enterprises

What are Containers?

Containers provide a lightweight, portable, and consistent packaging strategy that encapsulates an application and its immediate dependencies, but shares the host system’s kernel. By delegating isolation to the container runtime and kernel namespaces, containers start rapidly, use fewer system resources, and enable high-density deployments. This model is especially well-suited to modern, cloud-native applications composed of microservices, where rapid iteration, automated testing, and reproducible environments are priorities.

In practice, containers enable teams to build, test, and deploy software in a consistent environment from development through production. They align well with declarative infrastructure, continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipelines, and orchestration platforms that manage scaling, failover, and rolling updates automatically. While containers rely on shared kernel infrastructure, they still provide meaningful isolation at the process and namespace level, along with image-based reproducibility and immutability when combined with appropriate security controls.

- Lightweight images and fast startup

- Process-level isolation with shared kernel

- Consistent behavior across development, test, and production

- Strong ecosystem around OCI-compliant images and runtimes

Resource Usage and Performance

Resource usage is a central practical difference between VMs and containers. A VM carries the overhead of a full guest operating system, including its own kernel memory, device drivers, and system services, in addition to the host kernel. Containers share the host OS kernel and isolate workloads at the process level, which reduces memory footprints and accelerates boot and deployment times. In dense environments, containers typically yield higher VM-to-host density and faster provisioning cycles, enabling more agile capacity planning and experimentation. However, this efficiency can come with tradeoffs in areas like kernel-level security boundaries and compatibility with certain drivers or system services.

When planning capacity and performance, consider workload characteristics and operational requirements. Persistent, stateful services may reveal different tradeoffs than stateless microservices, and I/O-intensive tasks can behave differently under containerized stacks compared with traditional VMs. Storage strategies also diverge: VMs apply block storage to a guest OS image, while containers leverage container storage layers or persistent volumes that can be backed by separate storage services. The result is a distinct performance envelope for each model, and the right choice often comes down to how you balance density, control, and risk in your specific environment.

- VM baseline: stronger, hardware-enforced isolation but higher memory and storage overhead; longer boot times; broader compatibility with legacy software

- Container baseline: lower overhead, higher density, rapid start/stop cycles; dependency management is more portable but relies on host kernel features

- Orchestration impact: clustering and networking layers introduce their own overhead in both models, but containers often benefit more from horizontal scaling patterns

- Workload fit: long-running services with stable resource needs vs ephemeral, scalable microservices with frequent deployment cycles

Isolation and Security

The isolation model of VMs is fundamentally different from containers. VMs isolate workloads by encapsulating an entire operating system within a hypervisor, providing strong fault containment and independent kernel space. Containers isolate at the process and namespace level, sharing the host’s kernel. This shared kernel model can reduce attack surface in some scenarios but can also introduce risk if kernel vulnerabilities or misconfigurations expose multiple workloads to a single compromise. In regulated environments, the choice between VMs and containers often hinges on how organizations balance defense-in-depth, patch cadence, and the need for strict per-workload boundaries.

Security implications drive best practices across both technologies. For VMs, standard hardening approaches include patching guest OSes, enforcing strict network segmentation, and leveraging mature hypervisor security features. For containers, defense-in-depth involves securing the container runtime, limiting capabilities, using read-only images, enforcing image provenance, and adopting runtime security tools that monitor for anomalous behavior or privilege escalations. A pragmatic security posture often blends the two models—for example, running containers inside tightly controlled VMs or using container-native security controls in tandem with VM-based isolation for sensitive workloads.

Deployment and Operations

Deployment approaches reflect the fundamental architectural differences between VMs and containers. Virtual machines are typically deployed from hypervisor-managed images that include an operating system and application stack. Updates may involve replacing an entire VM or applying patch management within the guest OS. Containers, by contrast, are built as immutable images, deployed and updated via container runtimes and orchestration systems. This shift enables more automated, repeatable, and auditable release processes, aligned with modern DevOps practices and IaC (infrastructure as code) workflows.

Operational practices diverge accordingly. VM-based environments often rely on traditional IT infrastructure tooling for provisioning, monitoring, and disaster recovery, while container environments frequently require orchestration platforms that manage deployment patterns, health checks, rollouts, and self-healing. Kubernetes has emerged as a dominant model for containers, offering robust mechanisms for scaling, networking, and storage abstractions. When combined with cloud-native services, containers enable scalable, region-aware deployments, whereas VMs remain strong when you need broader OS compatibility, minor changes to governance processes, or vendor-provided ecosystems with established licensing models. As you design deployment pipelines, consider how teams will manage updates, backups, and incident response in each model.

Note: In practice, many organizations run a hybrid stack—VM-based environments for certain regulated workloads or legacy apps, and containerized services for modern, cloud-native components. This hybrid approach can leverage the strengths of both models while mitigating their weaknesses.

Scalability and Orchestration

Scalability patterns differ significantly between VMs and containers. Scaling a VM-based application typically involves provisioning additional VM instances, configuring load balancers, and potentially scaling the underlying hypervisor cluster. This approach can be effective for steady-state workloads but may involve longer lead times and heavier resource planning. Containers enable rapid horizontal scaling through orchestration platforms that automatically schedule containers across a cluster, monitor health, and adjust replicas in response to demand. This capability is particularly advantageous for microservices architectures and modern API-driven applications where demand can fluctuate quickly.

Orchestration introduces its own considerations. Container environments rely on networking overlays, persistent storage abstractions, and policy-driven security controls to maintain reliability as clusters expand. VM-centric deployments rely on orchestration at the VM and application layers, plus infrastructure automation for patching and scaling. In both cases, observability, centralized logging, and proactive performance management are essential to maintaining service quality as the system grows. The upshot is that containers tend to excel in dynamic, cloud-native ecosystems, while VMs often provide a stable, auditable foundation for long-lived or compliance-heavy workloads.

Cost Considerations

Cost modeling for VMs versus containers hinges on licensing, resource utilization, and operational expenditure. Virtual machines incur the overhead of running a full guest OS per instance, which can translate to higher memory and storage costs, as well as licensing expenses for multiple operating system images. Containers typically reduce per-instance overhead, enable higher density, and align with pay-as-you-go cloud pricing models. However, the cost advantages of containers depend on effective orchestration, storage management, and security tooling; misconfigurations or poorly designed container pipelines can erode the expected savings.

Beyond raw compute, organizations should consider the broader value proposition of each model. For workloads that must pass rigorous audits or require specific licensing constraints, VMs may deliver more predictable cost and governance. For cloud-native, stateless services that must scale rapidly, containers can reduce cost per request and speed up time-to-market. In modern practice, many enterprises tie these pieces together with cloud app services and managed platforms that abstract much of the operational burden, allowing focus on business outcomes rather than infrastructure minutiae.

Hybrid and Mixed Environments

Many organizations operate in hybrid environments that combine VMs and containers to match workload requirements, regulatory constraints, and organizational capabilities. Such mixed environments can leverage virtualization for stability and control while adopting containerization for new services, API layers, or CI/CD pipelines. A pragmatic architecture often places critical legacy and Windows-based workloads on VMs, while newer, microservices-based components run as containers on managed runtimes. This approach also supports incremental modernization, enabling teams to transition at a sustainable pace without disruptive rewrites or wholesale re-architecting.

Managing a hybrid stack benefits from clear governance and consistent tooling across boundaries. Infrastructure as code, centralized monitoring, and unified security policies help ensure visibility and control as teams mix VM and container paradigms. Carefully designed migration plans, with a focus on service boundaries and data persistence strategies, can help reduce risk while maximizing the advantages of both technologies in a cohesive platform strategy.

Migration and Modernization

For organizations embarking on modernization, a structured migration path is essential. A common approach begins with a thorough assessment of which components are best suited for containerization, followed by a phased lift-and-shift-to-container program or a replatforming effort that preserves business logic while changing the deployment model. Start by containerizing stateless services and gradually introduce stateful storage abstractions with persistent volumes and data management policies. Concurrently, retain critical security and compliance controls during each phase to avoid surprises in production.

Successful modernization also requires building new capabilities across teams. Developers, operators, and security professionals must align on image governance, CI/CD pipelines, and incident response playbooks. The result is a culture and architecture that leverage reusable components, reduce manual handoffs, and enable faster delivery cycles while maintaining the necessary controls for governance and risk management. This ongoing evolution is where cloud app services and managed container platforms often create the most business value, turning infrastructure into a strategic advantage rather than a cost center.

FAQ

Which approach should I choose for a new project?

Begin by assessing the project’s requirements: regulatory constraints, licensing terms, team expertise, and the need for rapid iteration. For new, cloud-native applications designed as microservices, containers with an orchestration platform are typically the preferred path due to fast deployment, scalability, and reproducibility. If you anticipate heavy reliance on legacy software, specialized OS requirements, or strict per-application governance, VMs may offer a safer, more familiar foundation. A hybrid plan—start containerizing the new components while preserving existing VM-based workloads—can provide a pragmatic, low-risk route to modernization.

Are containers secure enough for production workloads?

Containers can be secure in production when combined with proper controls: image provenance, minimal privileges, runtime security monitoring, and strict configuration management. Because containers share the host kernel, kernel vulnerabilities can affect multiple workloads if not mitigated. Therefore, pairing container security with robust host hardening, regular patching, network segmentation, and policy-driven access controls is essential. In high-safety environments, running containerized workloads inside tightly controlled VMs or using managed container services with strong security postures is a common pattern to balance agility and risk.

Can I run containers inside a VM?

Yes. A common and practical pattern is to run containers within VMs to combine the benefits of both models: the VM provides a trusted boundary and stable governance, while containers deliver lightweight, scalable application components inside that boundary. This approach is especially popular in environments that require strict isolation, legacy integration, or specific OS constraints. It also allows teams to leverage container tooling without fully exposing the likelihood of kernel-level risks to the entire fleet of workloads.

What are best practices for migrating from VMs to containers?

Start with a thorough inventory of applications and services, then identify candidates that are stateless or have well-defined interfaces suitable for containerization. Containerize these components first, implement CI/CD pipelines, and adopt a declarative deployment model with versioned images and immutable infrastructure. For stateful services, plan storage strategies using persistent volumes and consider Kubernetes or equivalent orchestration for lifecycle management. Maintain governance, security, and backup procedures throughout the migration to preserve reliability and compliance.