Now Reading: Blockchain vs Traditional Database: Do You Need a Blockchain?

-

01

Blockchain vs Traditional Database: Do You Need a Blockchain?

Blockchain vs Traditional Database: Do You Need a Blockchain?

Overview: Blockchain vs Traditional Database

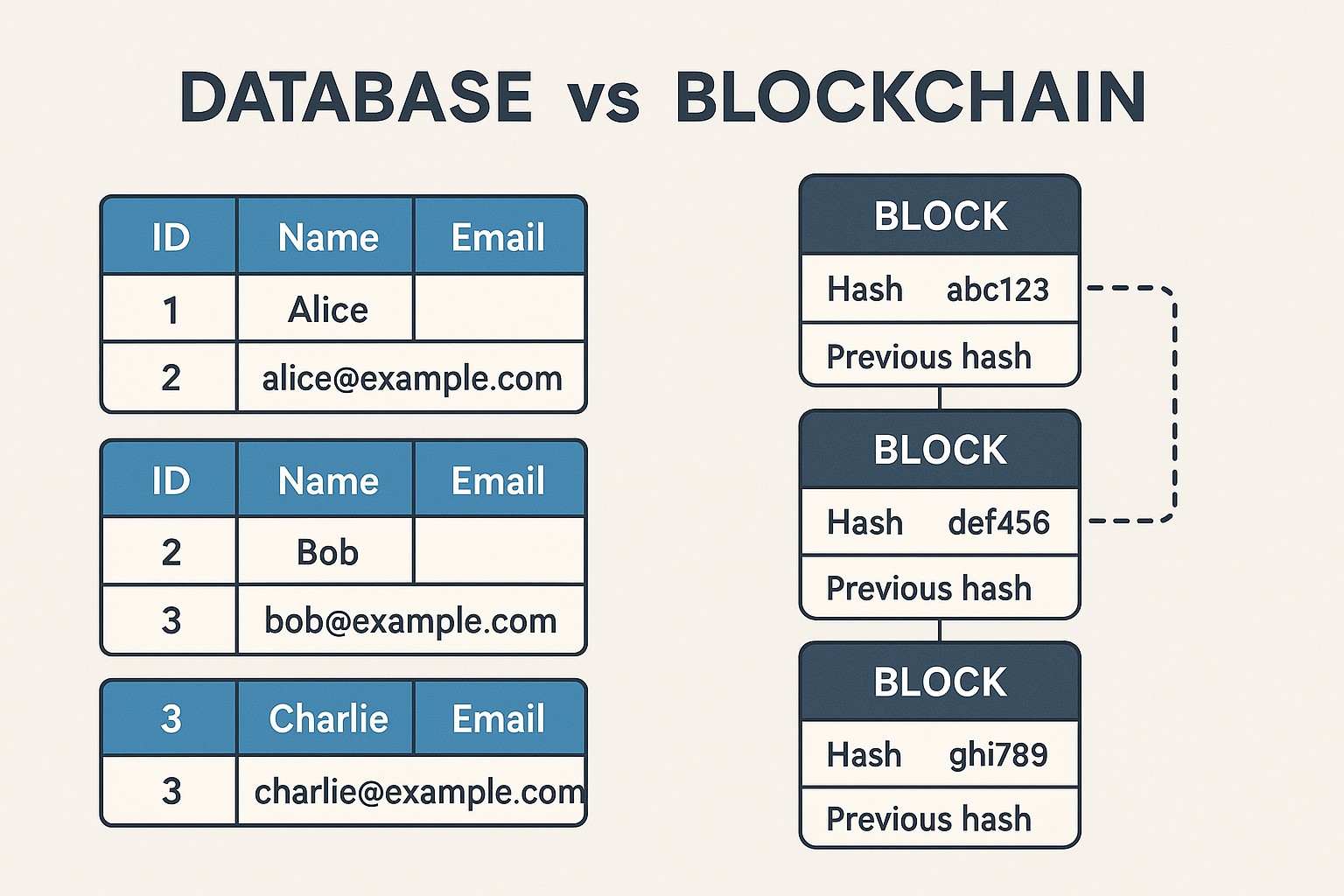

In many organizations, stakeholders face a choice between continuing with a centralized database architecture or adopting a blockchain-based ledger. This decision is not purely technical; it involves governance, trust, cost, and the nature of the data being managed. A traditional database centralizes control with one or more trusted administrators, enabling fast reads and writes and straightforward data modeling. Blockchain, by contrast, distributes an append-only ledger across a network of participants, creating a shared record that is difficult to alter without coordination. A clear scope and business objective are essential before selecting either approach.

To set expectations, blockchain does not automatically guarantee superiority in every dimension. For many business processes, a well-designed centralized database with strong access control and audit logging delivers the needed reliability, performance, and cost efficiency. Blockchain shines in scenarios where multiple parties require verifiable history, where trust is distributed and hard to centralize, or where tamper-evident records are a regulatory or operational requirement.

Architectural Differences: Centralized vs Decentralized data management

In a traditional database, data is stored in centralized stores controlled by a single organization or a trusted consortium. Transactions are validated by a centralized database engine that enforces ACID properties, supports rich indexing, and runs on conventional hardware. Maintenance, backups, and schema evolution are typically managed by a dedicated admin team, enabling rapid iteration and predictable performance.

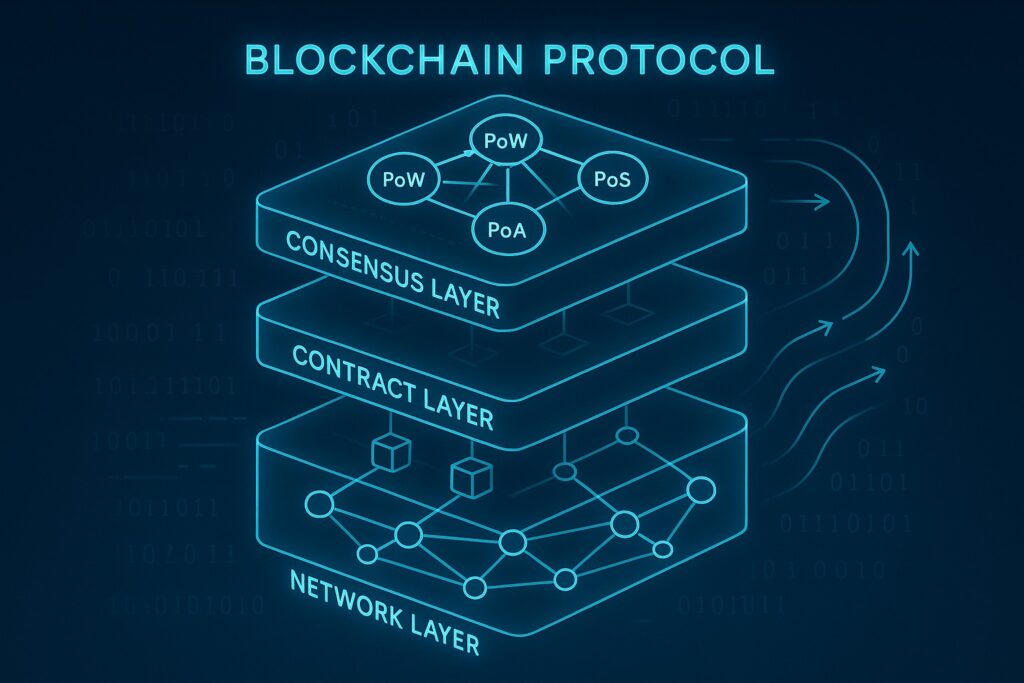

Blockchain, by contrast, introduces a distributed ledger where blocks of transactions are appended and agreed upon by consensus. Depending on the type, data may be replicated on every node or stored off-chain with cryptographic proofs anchored on the network. The governance model determines who can participate, who can validate, and how conflicts are resolved. These characteristics shape data availability, latency, and the way applications interact with the ledger.

Trust, Immutability, and Data Integrity

One of the most distinctive characteristics of blockchain is immutability: once a block is confirmed, altering it becomes difficult across the network. This property supports reliable audit trails and dispute resolution in multi-party ecosystems where trust is uneven. In a centralized database, tamper resistance relies on access controls, encryption, and monitoring; the system can still be altered by trusted administrators or compromised credentials. The decision hinges on whether permanent, verifiable history is essential or whether flexibility and agility are more valuable for the business.

Immutability comes with trade-offs. It can complicate corrections, deletions, or compliance requests that require data erasure. Organizations must plan how to handle mutable data, privacy requirements, and regulatory constraints while preserving the integrity guarantees of the ledger. Techniques such as off-chain storage, cryptographic proofs, or selective disclosure are commonly used to balance legal obligations with operational needs.

Performance, Scalability, and Governance Trade-offs

Performance characteristics differ substantially between blockchain and traditional databases. A centralized system can deliver sub-second response times and high write throughput with optimized software, indexing, and hardware. Distributed ledgers, especially those using consensus-based validation, introduce latency and throughput limits that scale with the number of participants and network conditions. These dynamics often translate into higher operational costs and more complex maintenance, which must be weighed against the benefits of shared trust and tamper resistance.

To bridge the gap, many organizations pursue hybrid architectures that place core transactional workloads in a fast database while anchoring critical events or audit proofs on a blockchain. This approach preserves performance where it matters most while enabling cross-party verification and tamper-evident audit trails. Hybrid designs require careful governance arrangements, data mapping, and synchronization strategies to avoid data drift and ensure consistency across layers.

- Latency and throughput differences across network sizes and consensus models

- Governance and access control complexities across multiple organizations

- Data mutability versus immutability expectations in different domains

- Operational costs, including energy use and ongoing maintenance

Use-case patterns: When blockchain adds value

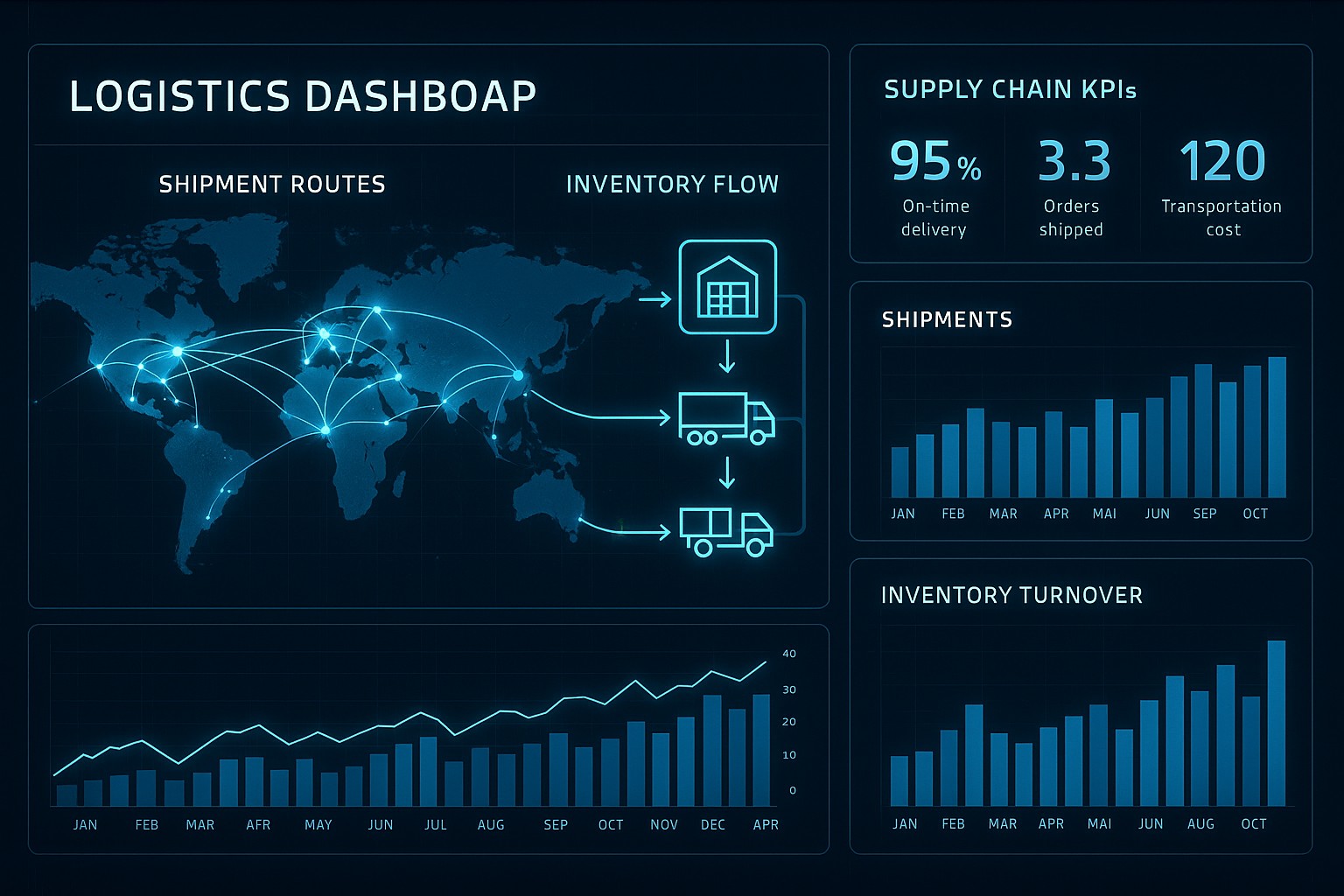

Blockchain is not a universal solution; its value emerges when there is a need for shared truth across independent participants. Common patterns include cross-organization asset tracking, provenance for high-value goods or pharmaceuticals, and dispute resolution in multi-party workflows. In these contexts, a tamper-evident ledger, time-stamped events, and traceability can reduce reconciliation costs and enable more transparent governance.

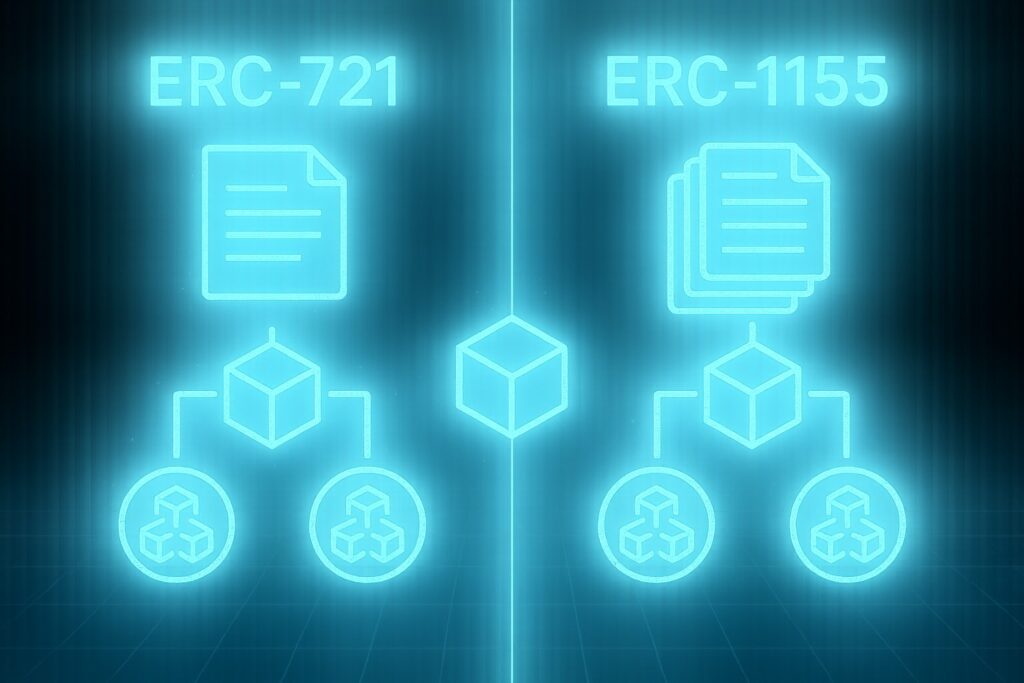

Beyond pure governance, blockchain-enabled architectures can facilitate smart contracts, automated enforcement of agreements, and more robust auditability. However, for many linear, internal processes, a traditional database with strong access control and integrated analytics remains simpler and more cost-effective. The key is to map business requirements to the ledger’s unique properties and identify where immutability, decentralization, or verifiable history deliver measurable value.

Data governance, privacy, and regulatory considerations

When data crosses organizational boundaries, governance becomes more complex. Ownership, consent, and retention policies must be defined upfront, and governance bodies must agree on who can write, read, or verify data. Blockchain’s shared ledger often means data is harder to erase or relocate, so planning for privacy by design is essential. Enterprises should consider whether data should be stored on-chain or referenced via cryptographic proofs or pointers to off-chain storage. In sectors like healthcare, questions about what is big data in healthcare surface, underscoring the need for privacy-preserving analytics and compliant data sharing across institutions.

Regulatory requirements such as GDPR, HIPAA, and industry-specific standards influence architecture choices. Organizations frequently employ privacy-preserving techniques like data minimization, pseudonymization, and selective disclosure to limit exposure while maintaining auditability. A comprehensive data governance framework, including policy, roles, and controls, helps ensure that technical decisions align with legal obligations and business risk tolerance.

- Data ownership and consent management across multiple parties

- Right to be forgotten or data deletion in immutable ledgers using compliant patterns

- Auditability, logging, and traceability without exposing sensitive information

- Regulatory alignment and ongoing compliance monitoring

Migration, integration, and implementation challenges

Transitioning from a traditional database to a blockchain-enabled architecture requires careful planning and incremental execution. Organizations should begin with a scoping exercise to identify data assets, interdependencies, and regulatory constraints. A proof-of-concept or pilot helps validate assumptions about latency, throughput, and cross-party governance before large-scale investment.

Practical paths include hybrid designs, where the core transactional layer remains centralized while blockchain serves as an immutable audit log or verification layer. Pilot programs should emphasize interoperability with existing systems, data quality, and change-management aspects. Building a robust governance framework and a clear migration plan reduces risk and accelerates realization of the intended benefits.

- Assessment and scoping of data, stakeholders, and regulatory requirements

- Prototype, pilot, and performance validation

- Incremental migration with parallel operation and reconciliation

- Vendor selection, risk management, and ongoing governance

Conclusion: A decision framework for blockchain adoption

Choosing between a traditional database and a blockchain-enabled solution is a decision about risk, trust, and organizational dynamics as much as it is about technology. By clarifying the business problem, assessing data provenance needs, and weighing performance and cost trade-offs, decision-makers can identify where tamper-evident ledgers deliver real value and where conventional data stores remain the better fit.

In practice, many organizations adopt a pragmatic, hybrid approach that preserves performance for day-to-day operations while enabling cross-party verification and immutable records for critical events. The right choice depends on the granularity of control, the number of participating entities, regulatory demands, and the long-term data strategy. A clear roadmap, stakeholder alignment, and measurable success criteria are essential to avoid scope creep and overspend.

What is blockchain in simple terms?

Blockchain is a distributed ledger technology that records transactions across multiple participants in a way that is resistant to tampering. Each transaction is grouped into a block, cryptographically linked to the previous block, and validated by a consensus process. The result is a shared, append-only record that can provide verifiable history without relying on a single trusted administrator.

Is blockchain necessary for all data management needs?

No. Many use cases benefit from centralized databases with strong controls, fast queries, and straightforward data modeling. Blockchain adds value when there is distributed trust, a need for tamper-evident history, or cross-party reconciliation. For internal, high-speed operations, a conventional database is typically more efficient and cost-effective.

How do privacy and regulatory requirements work with immutable ledgers?

Immutable ledgers can pose challenges for data privacy and right-to-erasure. Organizations address this by keeping sensitive data off-chain, storing only references or hashes on-chain, applying pseudonymization, and implementing access controls and data lifecycle policies. Regulatory compliance often requires careful design choices and documentation to demonstrate accountability and data provenance.

What are typical costs and ROI considerations?

Costs include development, network infrastructure, governance overhead, and ongoing maintenance. ROI depends on the degree of cross-party coordination required, improvements in reconciliation time, and risk reduction from tamper-evident records. For many teams, the operational overhead of a blockchain can be justified only if collaboration and trust across multiple entities are critical to the business process.

How should an organization start a blockchain project?

Begin with a clear business objective and a small, well-scoped pilot to test core assumptions about data flow, latency, and governance. Prioritize hybrid architectures that combine a fast database with an immutable verification layer, and establish a governance model with defined roles, data ownership, and success metrics. A phased approach with measurable milestones reduces risk and increases the likelihood of delivering tangible value.